How Can Municipalities Rethink Policing?

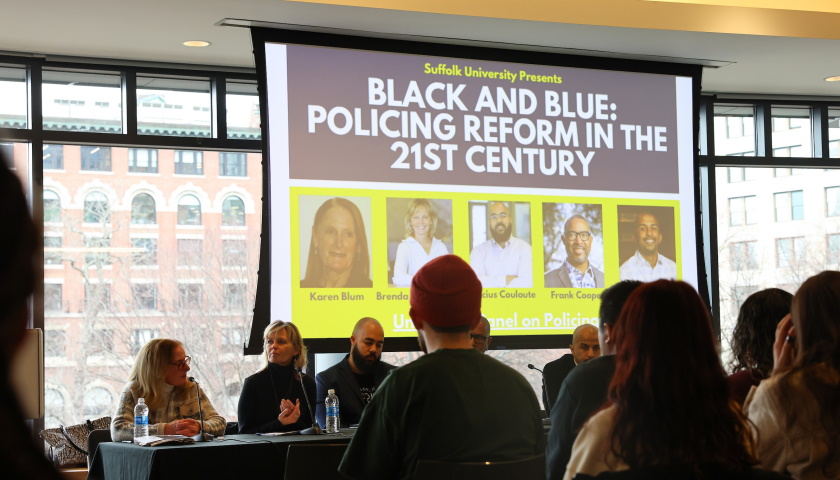

The complex questions raised by the killing of Tyre Nichols by Memphis police officers served as the inspiration for a thought-provoking panel discussion on February 27 that drew faculty experts from across the University community. [Watch the event.]

Their verdict: The road to much-needed reform is steep, because so many factors contribute to disparities in policing.

“What has to change is both the rulebook and the culture,” said Carlos Monteiro, assistant professor of sociology & criminal justice. “And the challenges,” said Brenda Bond-Fortier, professor of public service, “are not solely on the shoulders of the police.”

‘Systemic devaluation of Black life’

Lucius Couloute, assistant professor of sociology & criminal justice, set the stage by sharing statistics on policing. Every year roughly 1,000 people are killed by on-duty police officers—a disproportionate number of whom, he said, are Black and often unarmed. While Blacks make up 13.6% of the population, 32% of unarmed people killed by police are Black. He pointed to a Harvard study showing that in police encounters, Blacks are killed at a rate almost three times that of whites.

“One of the foundational causes of inequality with respect to police killings is the systemic and historical devaluation of Black life,” he said, as well as “long-standing myths about inherent Black criminality.” Social and psychological research consistently shows that Blacks are viewed as less friendly, less intelligent, and more threatening than their white peers, he said, which impacts how their communities are policed.

Monteiro, whose research focuses on corrections, said that with the current focus on professionalized and militarized policing there’s significantly less “walking the beat,” and police officers in stressful situations often do not know the people and neighborhoods they are operating in.

"When officers are pulled from the beat and placed in cruisers, and when residents in less affluent communities are only seeing officers in high stress situations: responding to a call, with sirens blaring, or arresting a member of the community, in what are often tense and traumatic situations, the effects are counterproductive and damaging for everyone involved including the officers," he said.

Legal remedies—and roadblocks

Professor Frank Rudy Cooper, a former Suffolk Law faculty member now teaching at the University of Nevada’s Boyd School of Law, outlined a series of Supreme Court cases which, he said, unfairly protected police officers’ pretextual use of search and seizure powers to racial profile or allowed police to commit acts of violence that were unnecessary or disproportionate to the threats they faced.

In Graham v. Connor (1989), he said, the court held that when using force the police need only meet the standard of what a reasonable officer might do—and that an officer’s underlying evil intent or motivation could not be a consideration.

Suffolk Law Professor Emerita Karen Blum, an expert on police misconduct law, described the challenges presented by qualified immunity, the legal defense that shields police officers who commit constitutional violations from being held personally liable for monetary damages as long as they haven’t violated “clearly established” law.

The Supreme Court, she said, has made this standard so “impenetrable” by plaintiffs in civil rights cases that “it's become almost an absolute immunity. This makes it nearly impossible for plaintiffs to prevail,” she said. Since 1982, the Supreme Court has confronted qualified immunity in over 30 cases and plaintiffs have won just three times.

‘You need multi-level change’

Bond-Fortier, the author of Organizational Change in an Urban Police Department: Innovating to Reform, said that it takes even a small police organization about ten years to reform itself. Across the country, there are more than 18,000 separate police organizations, and each is directed by legal mandates in their own states, local municipal policies, and a wide variety of local police union regulations.

“You need multi-level change in order to actually shift the way that officers behave,” she said, including changing how officers are recruited, hired, on-boarded, and trained, so that community needs and wants are better reflected.

Mental health calls pose additional challenges, Monteiro said, because officers may respond to what they see as noncompliant behavior by using force. He advocated for the development of alternative responses, including mental health and substance abuse professionals who could assist in de-escalating volatile situations.

“We have programmed people to call 911, and the only people who respond 24 hours a day, seven days a week are the police,” Bond-Fortier added. “As we talk about police reform and all the things we can do to fix the police, we also have to expand our thinking. Municipal and state leaders have a role in thinking about what the future of safety is, and how we place people and their expertise [to better] serve the needs of the community.”

Media Contact

Greg Gatlin

Office of Public Affairs

617-573-8428

[email protected]