“There was a time when you could tour an entire plantation and not hear slavery mentioned once,” says Professor Robert Bellinger.

According to Bellinger, Director of Suffolk’s Black Studies Program, the history of American plantations has long been centered around the owners, their families, and their wealth. But those stories are interconnected with the stories of the enslaved people who made that wealth possible. These narratives are often complex, competing, and conflicting. Telling them is a challenge for historic sites everywhere, says Bellinger.

Middleton Place, a former rice plantation outside of Charleston, South Carolina, that boasts the nation’s oldest landscaped gardens, embraces the challenge. A statement on its website acknowledges the dichotomy of its past, reading in part:

...When we stand on the same land as generations of the enslaved and the free, take in its exquisite beauty and its inherent brutality, we understand that the stories of Middleton Place are American stories. Black stories. White stories. Essential, life-changing human stories…

This summer Suffolk University History major Nicholas Nunez became part of that story during an internship at Middleton Place. He helped reinterpret an essential piece of the plantation’s agricultural history: an exhibit on rice cultivation, the site’s main crop.

Stepping back in time

When he first arrived Nunez spent time exploring the expansive grounds, developed over centuries in large part by the enslaved people and their descendants who lived and worked on the plantation. As a Black Studies and Biology double minor, he was fascinated by the heritage breeds of animals and plants at the site, which originally were cultivated by Africans and African Americans. Some date to before the American Revolution.

“I read multiple books on rice cultivation and history,” says Nunez. “Often only Asian and European expertise is recognized, but many African populations have strong rice-growing traditions and knowledge.”

Nunez rewrote portions of the exhibit text to acknowledge the effort and agricultural skill of Africans and African Americans. He also recommended some subtle but vitally important changes in the language used throughout the exhibit.

“Changing passive language such as ‘crops were harvested’ to language that attributes the work to enslaved people acknowledges the reality of what really took place,” says Nunez.

Nunez also learned about the watermen of Middleton Place, enslaved men who were responsible for transporting crops to market.

“Shipment receipts show that the enslaved watermen were trusted to operate the schooners and move the crops by themselves, which shows a high level of autonomy for that time,” says Nunez.

Beyond the fields

Middleton Place has striven to incorporate these narratives into their larger story since they opened as a historic site in the 1970s, says Engagement Director Carin Bloom. The plantation has always employed interpreters in the stable yards demonstrating artisan work such as blacksmithing, and throughout the gardens and in the main house describing life over many generations. In-house scholars are constantly researching and updating the exhibits and tours, says Bloom.

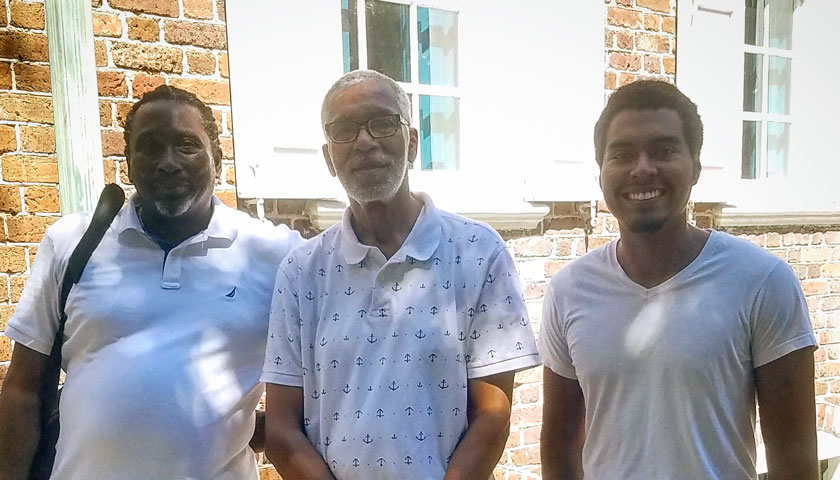

“The internship opened my eyes to jobs in public history, both in research and administration. I was able to work with everyone, including the CEO, engagement director, groundskeepers, and interpreters,” says Nunez. Here, Nunez (far right) pauses outside a plantation building with Professor Robert Bellinger and Middleton Place descendant and tour guide Ty Collins (from @middletonplace).

The plantation started holding reunions of all descendants—of the Middleton family and the enslaved and freedmen and freedwomen workers who lived there for generations—in 2006. Staff developed a “Beyond the Fields” tour dedicated to the experiences of the enslaved people and freed workers who shaped Middleton Place, and a documentary of the same name was filmed at the reunion in 2016. Bellinger, who traces a branch of his family back to Middleton Place, participated in the celebration and contributed commentary for the film.

“That was my first visit and the beginning of learning about the plantation’s history and culture,” says Bellinger. “Middleton Place is very different to what we have in New England, and I wanted to give my students the opportunity to see American history from another vantage point.”

Yesterday, today, and tomorrow

As Nunez worked on redesigning the rice exhibit at the plantation’s Mill House, Bellinger conducted research as a summer visiting scholar. Their journey into the past has striking relevance today.

“This year marks the 400th year of the presence of people of African descent in British North America,” says Bellinger. “When you look at the backlash to the New York Times’ 1619 Project, that ‘examines the many ways the legacy of slavery continues to shape and define life in the United States’ and clashes over Civil War monuments and other statues in recent years, you can see how contentious this history is and how we’re still struggling to tell the story of the United States.”

“Having a Black Studies and History education means I have a complex perspective on Charleston. When I visited urban plantations we would walk into marvelous rooms decorated with Chinese porcelain and European fabrics and furniture and hear about elaborate dinners and social events. It’s easy to get lost in those romantic details, but I am always aware that the wealth on display wasn’t made under moral standards,” says Nick Nunez, pictured at the Nathaniel Russell House Museum in Charleston, South Carolina (via @middletonplace).

“People say ‘don’t make it a race thing,’ but a lot of people don’t know their American history. Black Studies is about giving agency to black people and recognizing the history of the community. History doesn’t start and end with slavery. We’re learning to recognize stereotypes and correct false narratives and misinformation,” says Nunez.

At Middleton Place, Nunez learned how to make unvarnished historical truths more palatable to the public. One lesson? Never put the visitor in the shoes of the historical figure, he says.

“Rather than saying ‘you would be this type of person’ we should describe the types of people who would have existed, their lives and behaviors, and leave the visitor to make those personal connections without feeling defensive,” says Nunez.

Nunez kicked off his internship by helping out at the plantation's 4th of July celebrations.

For Bloom and Middleton Place, coming to grips with the past means moving beyond specialized tours like “Beyond the Fields” to incorporate more diverse perspectives at every turn. “We don’t want to segregate those narratives from the rest of the site,” she says.

“Nick really succeeded in reimagining the entire exhibit,” says Bloom. “He gave us real things we can implement to offer a better, more inclusive picture of life at Middleton Place.”

“I don’t know if he’s aware of the ripple effect his project can and will have on the rest of the site. Now we’re looking at applying for grants to do a bigger revamp using Nick’s project as a springboard for improving all the narratives we’re telling.”

Contact

Greg Gatlin

Office of Public Affairs

617-573-8428

Andrea Grant

Office of Public Affairs

617-573-8410