Architect of Workplace Bullying Legislation Wins Lifetime Achievement Award

Law Professor David Yamada, the architect of a bill that offers workers a legal remedy for health-harming workplace bullying, received the Bruce Winick Award for outstanding contributions to the field of therapeutic jurisprudence in July at the International Congress on Law and Mental Health in Rome.

The award recognizes Yamada’s contributions to the field of therapeutic jurisprudence, which analyzes whether laws and legal systems promote or detract from the advancement of psychological well-being and human dignity. Therapeutic jurisprudence gleans insights from social science to make the law more humane and effective, according to Yamada. The Bruce Winick award is named for a cofounder of the therapeutic jurisprudence school of social inquiry.

Yamada has written about therapeutic jurisprudence as providing “valuable lessons for a healthier, more meaningful practice of legal scholarship.” He recently completed his term as founding board chair of the International Society for Therapeutic Jurisprudence, which was conceived during a workshop Yamada hosted at Suffolk in 2015. His research in the area of therapeutic jurisprudence is focused on workplace bullying.

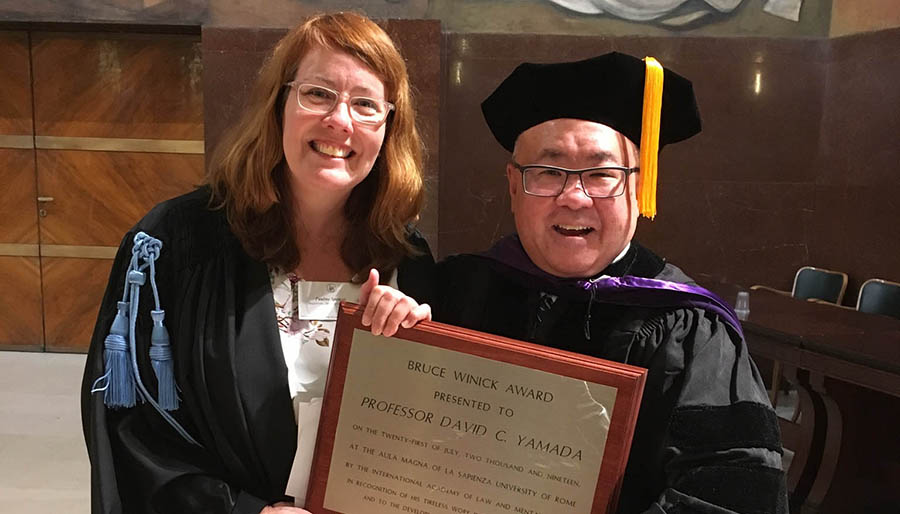

Magistrate Judge (Melbourne, Australia) Pauline Spencer presents Professor David Yamada with a lifetime achievement award.

Addressing Workplace Bullying

Researchers estimate that one-third of America’s workers have been a target of workplace bullying at some point during their careers—but unlike most countries in Europe and South America, the U.S. lacks laws to address the phenomenon. In 2000, Yamada wrote an article, The Phenomenon of 'Workplace Bullying' and the Need for Status-Blind Hostile Work Environment Protection, for the Georgetown Law Journal.

He then wrote and has been working to promote the Healthy Workplace Bill in state legislatures across the country. The bill gives severely bullied workers a legal claim of action and creates legal incentives for employers to prevent and respond to workplace bullying.

The bill’s language is modeled on the sexual harassment terms under Title VII and doesn’t make it overly easy to sue. “I set the bar higher for recovery—you need to show intent to harm,” Yamada says. “We need to open this door carefully.”

Yamada emphasizes the difference between incivility and abusive behavior. “Workplace bullying is repeated, malicious, health-harming behavior. Not a bad day in the office or a dust-up. It’s about intentional harm and targeted victims.”

In Massachusetts, 109 of the 200 state legislators have cosponsored the legislation, according to Yamada, including one of his former students, State Rep. Danielle Gregoire, JD ’06.

Gregoire says that the law professor’s efforts on policy in the workplace have had a ripple effect across the country and in Massachusetts. “It was at his urging that I cosponsored his legislation to ban workplace bullying, and I'm happy to continue our work together to see this bill become law so we can better protect Bay State employees.”

Practical outcomes

One example of the therapeutic jurisprudence movement’s impact is the creation of problem-solving courts for veterans. Servicemen and women returning from tours of duty might be suffering from depression and post-traumatic stress disorder that could contribute to their engaging in illegal behavior, according to Yamada. Rather than processing them through the traditional criminal justice system, some jurisdictions have created veterans courts to divert them into treatment and rehabilitation programs.

There’s not a lot of pretension in the field of therapeutic jurisprudence, according to Yamada.

“It’s more about using research and insights to produce practical legal and policy outcomes,” he says. ”Look at bureaucratic forms, for example. Do they lead to resolution of a problem or promote conflict? One therapeutic jurisprudence study looks at ways to improve a state’s marital dissolution form and revises it to promote a peaceful and less stressful resolution.”

Another study looks at the amount of time judges spend with defendants explaining their rulings. Some judges step down from the bench and sit at a table with the defendant to explain the sentence they are imposing, which creates a more humane setting.

“It provides some dignity to that individual—and it has an impact on how likely the offender is to reoffend,” says Yamada. ”The study shows that if a judge spent three minutes or more going over a disposition, the defendant was less likely to become a repeat offender.”