As she led students on a walking tour of Beacon Hill, History Professor Kathryn Lasdow explained that the way the buildings, alleys, and streets converged created places for people to hide—a boon to the white and black abolitionists providing sanctuary to people escaping from slavery in the 19th century.

“One student said: ‘I’ll show you the best part’ and led the group to a narrow, tunnel-like alley that leads to the African Meeting House,” now part of the Museum of African American History and its Black Heritage Trail.

The sheltered Holmes Alleyway was part of the Underground Railroad, and walking through the narrow passage today conjures up a time in our country’s history when human beings were treated as chattel and Boston provided a refuge.

“I love it when I’m teaching them and they turn around and teach me,” says Lasdow, director of Suffolk’s Public History concentration, recalling the moment. “One of the things that excites me about Suffolk students is they have this energy and this passion for the material, but a lot of the work we do in public history is about how we translate that passion into something we can share with people.”

Beyond the American Revolution

The student who led Lasdow and classmates to the Holmes Alleyway was Jennifer Steele, Class of 2019.

“When I heard that Boston had a Black Heritage Trail, I told myself, ‘I have to take the tour because it has history you won't ever hear of,’” says Steele. “People will not always tell you black history; you have to find it sometimes,” she says.

Steele’s interest in the history of Beacon Hill and the African Americans who lived there stems from “both being an African American woman and loving history.”

A place of refuge

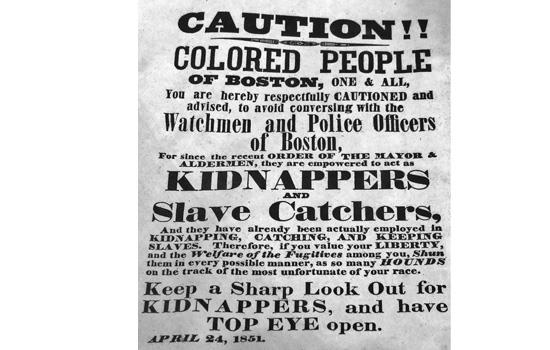

People fleeing slavery in 19th century America found a haven on Boston’s Beacon Hill, where an established African American community, abolitionist activism, and the architectural infrastructure combined to create a supportive environment for travelers on the Underground Railroad.

The stories of that history live on through the efforts of the National Park Service and the Museum of African American History, located just steps away from Suffolk's downtown Boston Campus.

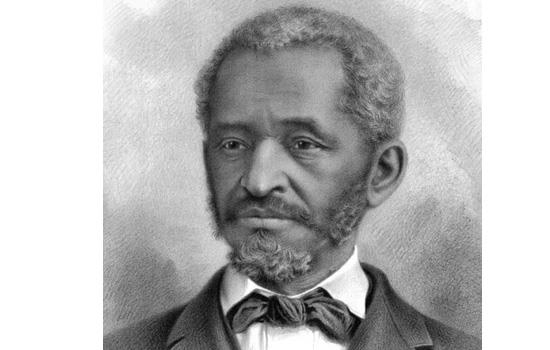

Stories like that of Lewis Hayden, who after escaping slavery sheltered others fleeing to freedom. When slave catchers banged on his door demanding that he give up a refugee couple, he threatened to torch a cask of explosives if they didn’t leave. They retreated.

He is but one of the men and women who risked their lives for the sake of others. The museum’s Black Heritage Trail [PDF] retraces their steps as it winds its way through the brick and cobble streets of Beacon Hill.

“The men and women who lived here in the 19th century led a social revolution, a revolution that was felt locally in the form of one of the United States’ first true civil rights movements and nationally in the fight against the institution of slavery,” says Suffolk alumnus Shawn Quigley, a ranger with the National Parks of Boston.

Surrounded by history

Suffolk’s location immerses students in significant American history, says Professor Robert Bellinger, director of the Black Studies Program. “It’s exciting to be in walking distance of so many sites and monuments. The Black Heritage Trail is a way to explore the Boston of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the museum is a resource for learning and possible internships.”

The centerpiece of the Museum of African American History is the African Meeting House, the oldest standing black church in America and a significant site in the abolitionist movement. The museum acquired the meeting house, a National Historic Landmark, in 1972.

“To be able to go into the building where abolitionists Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Maria Stewart spoke; there’s no way to get this experience anywhere else,” says Bellinger.

Walking in their footsteps

Quigley was an intern at Old South Meetinghouse while studying history at Suffolk. He had chosen Suffolk due to his interest in the American Revolution and its roots in Boston. But soon he became fascinated with the central role Beacon Hill and its African American residents played in the transformation of America. Now he leads tours of the Black Heritage Trail and works at Faneuil Hall.

Quigley begins his tour opposite the Massachusetts State House at the monument depicting Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment.

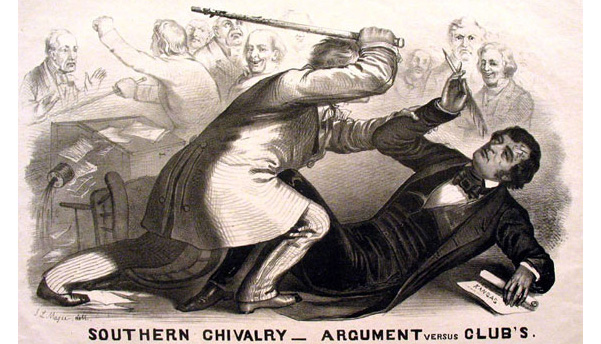

The bronze sculpture by Augustus Saint Gaudens depicts the regiment of African American soldiers decimated in an attack on Fort Wagner in Charleston, South Carolina. The battle was lost, but the soldiers’ courage inspired thousands of African Americans to join the Union Army.

“The man on the horse is white. The men on the ground are black,” says Quigley. ”That is because the United States Army during the American Civil War was segregated. This was not something that was just limited to the American Civil War. This extended all the way past World War II until 1948.”

Shaw was one of the multitude who died in the Fort Wagner assault, and the monument on the edge of Boston Common initially was focused solely on the white colonel.

“Shaw’s parents were ardent abolitionists. They detested the institution of slavery,” says Quigley. ”Shaw's father told Saint Gaudens: ‘If you're going to do a monument to my son, you have to include his men as well.’"

Points of view

Monuments and how they depict history are among the topics addressed in the study of public history.

Steele, recalls class discussions about the sculpture and the impression of inequality it conveys. Yet she doesn’t think Shaw should be omitted from the scene or made less prominent “because that doesn't tell history. It looks like he was better than the black soldiers, but he just had a higher rank. Every team needs a leader, and he was just their leader.”

Like Steele, Nicholas Nunez, Class of 2020, is interested in the “hidden” aspects of American history.

“Black history and public history are important to give people the full history of America, and who is telling the story is as important as what the story is,” says Nunez.

Much American history is written from a white perspective, and while Nunez says it’s important to hear that point of view, it’s also critical to see what black people have to say. “You can then gauge how different people perceive a specific event,” he says.

Making history relevant

Bellinger emphasizes to students the importance of interpretation and the value of different perspectives when studying history, particularly the perspective of those actually engaged in the events.

“Giving agency to African American people is important to history of the city and the country,” he says.

He returns to the idea of public history.

“Being close to so many exciting examples of public history—from the Museum of African American History to the freedom Trail—allows us to engage our students in a meaningful way. Hopefully more students will recognize the important role that history plays and the many ways that studying history in the undergraduate years can benefit their professional development.”

Another way that Suffolk supports public history is through the Clark Collection of African American Literature, directed by Bellinger, which aims to gather the works of all black American writers from the eighteenth century to the present. The collection was established in 1971 in collaboration with the Museum of African American History and the National Park Service and is housed in the University’s Sawyer Library.

For the people

Says Lasdow: “One of the big questions in public history is: How do we make history relevant in a changing world? History is always changing, so we may think that we have it right, and then ten years from now we find another piece of the puzzle, and the story changes.”

She says that public history is important because “it takes the work that historians and people interested in history do with books and in the archives and translates it to the broader public. Boston is an incredibly rich place to do that work because we’re not only surrounded by the history on the streets and spaces around campus, but we also have a really wonderful University archive here on campus and we have the faculty and the interested students to help initiate these projects. So when we’re thinking about why history matters and who history’s for, public history plays an incredibly important role because it’s the vehicle through which we can do that storytelling. And students like Jen [Steele] and her classmates …will get to participate in that conversation and in that work.”

Contact

Greg Gatlin

Office of Public Affairs

617-573-8428