About

Congressman Moakley served as a state representative (1953-1960), a state senator (1965-1970), a city councilor (1971-1972), and a member of Congress (1973-2001) before succumbing to leukemia in 2001.

For additional information about Moakley's life and career, please consult the following resources:

- Brief biography [PDF]

- Timeline of Moakley's life

- In Service to His Country video

- Moakley and El Salvador video

- Moakley Papers collection guide

Early Life

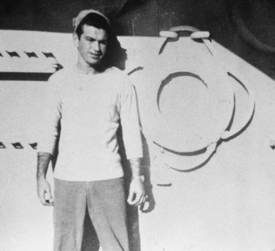

John Joseph "Joe" Moakley grew up in the tight-knit, blue-collar neighborhood of South Boston during the Great Depression. His tough, fair-minded father, Joe, taught him to stand up for what was right. He watched his compassionate and deeply religious mother, Mary, care for others. On the street corners, he learned loyalty and values. At the age of 15, he altered his birth certificate to enlist in the U.S. Navy. He served as a Seabee in the Pacific theater during World War II. After the war, he took advantage of the GI Bill® to attend Newman Prep and the University of Miami. In 1950, he began two lifelong passions: a romance with Evelyn Duffy and a career in public service.

Massachusetts Politics 1950-1972

In 1950, Joe Moakley was a well-known, well-liked football star and veteran with a college education. But to Moakley, the most interesting sport was politics. His friends and fellow GIs urged him to run, as "someone who represents us." So he ran for state representative of South Boston in 1950—and lost. Undeterred, he ran again in 1952 and won.

In 1956, Moakley graduated from Suffolk University Law School and in 1957 opened his law practice in South Boston with fellow graduate Dan Healy. In 1960, Moakley ran unsuccessfully for state senate against John Powers. Out of office, he practiced law until winning the senate seat in 1964.

In 1970, Moakley threw his hat into the congressional race to succeed the legendary House Speaker John McCormack. The packed race was won by Louise Day Hicks. Moakley ran for Boston City Council, winning the highest vote total on record. In 1972 he narrowly defeated Congresswoman Louise Day Hicks for the Massachusetts Ninth District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Over these 20 years, as a state representative, state senator, and city councilor, Joe Moakley built his skills and reputation as a "bread-and-butter politician." He worked tirelessly for all his constituents, finding jobs and housing and filing legislation to assist and protect his working-class district. At the same time, Moakley established an agenda of issues that he would carry through nearly 50 years of public service: environmental protection, social justice, job creation, historic preservation and economic development. While his ability to build consensus made him effective, he also demonstrated a willingness to stand for what he thought was right, however unpopular.

Congressional Years: 1973-2001

Elected to the United States Congress in 1972, Joe Moakley expanded his impressive constituent services to meet the needs of the large and diverse Massachusetts Ninth Congressional District. At the same time, he entered his apprenticeship to Tip O'Neill and the national Democratic Party. His core agenda remained the same: meeting constituent needs, protecting the environment, social justice, and creating jobs and housing through government-funded projects.

While continuing to work towards revitalizing Boston's waterfront, he embraced the concerns and agendas of his entire district, even as its boundaries changed. The Miles Standish Industrial Park was rescued when GTE located its $4.3 billion Army contract operation in Taunton. The Town of Walpole fought off a sludge landfill with his assistance. Also, numerous historic sites, including Dorchester Heights, the African Meeting House, the USS Constitution and the Old State House we protected and renovated with funding he secured.

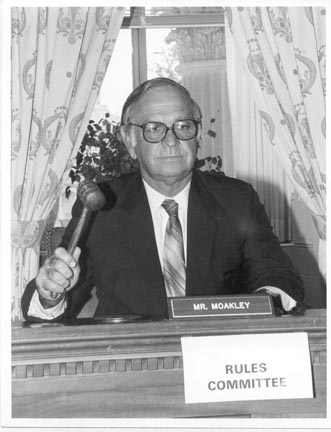

Congressman Moakley's interpersonal skills and strong work ethic made him a popular and capable member of the Personnel and Rules Committees. In 1989, he was appointed chair of the powerful House Rules Committee. In addition to his important work, Moakley loved to meet with his constituents. He visited each town in his district every year, holding open "office hours" at the local post office. In 1983, Salvadoran refugees seeking asylum in his district told him their stories of torture and terror and of their fear of retribution should they return to their homeland. Moakley's embrace of the Salvadoran immigration cause transformed him from a politician to a statesman. He is most well-known for his courageous leadership of the investigation into the murders of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper and her daughter in El Salvador in 1989. Moakley also participated in or led delegations to China, Ireland, Egypt, Israel, and Cuba.

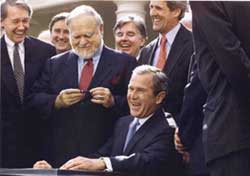

In the 1990s, Congressman Moakley championed his agenda while fighting personal battles, enduring a liver transplant, the death of his beloved wife, Evelyn, and, finally, incurable leukemia. Despite these challenges, he continued to ably and energetically represent his district and survived to see many of the causes he championed come to fruition, including the end of war and growth of democracy in El Salvador.

Moakley's Involvement in El Salvador

Moakley played an important role in moving El Salvador beyond repression and rebellion to peace. In doing so, he forged a lasting relationship with the people of El Salvador.

Immigration and Human Rights

Joe Moakley often held open office hours in towns in his district, meeting constituents, answering questions, and hearing their complaints and requests for help. These meetings gave ordinary people direct access to their government while helping Moakley keep tabs on constituent concerns.

In 1983, at a post office in Jamaica Plain, Moakley heard from Salvadoran refugees who feared being deported. El Salvador was mired in a bloody civil war, they told Moakley, and deaths squads were murdering or “disappearing” tens of thousands of civilians. The refugees feared that they would be harmed by the Salvadoran government and its allies if they returned. Moakley verified the accuracy of these stories, then took action.

For six years, he fought to pass legislation that would allow Salvadoran immigrants to live and work in the United States until it was safe to return to their country. Finally, he used leverage as the new chairman of the Rules Committee to amend the Immigration Act of 1990 to grant Temporary Protected Status to Salvadorans who had fled their country. The bill passed, implementing measures that have saved hundreds of thousands of lives from potential harm—and which are still in use today.

The Moakley Commission and the Jesuit murders

Moakley’s reputation for fair dealing and a genuine willingness to cooperate across party lines made him one of the most popular and trusted leaders in the Congress. So when Speaker of the House Tom Foley launched a congressional investigation into the 1989 murders of six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter in El Salvador, he appointed Moakley to lead it. Congress had authorized billions of dollars in economic and military aid over the years to El Salvador, and, with the Salvadoran military and the leftist guerilla group FMLN accusing one another of the atrocity, U.S. legislators demanded answers.

With his knowledge of El Salvador’s recent history, his willingness to speak to anyone in pursuit of the truth, and a dogged determination to find justice, Moakley was able to prove that the murders had been carried out by the Salvadoran soldiers. The Moakley Commission's final report hinted that culpability could extend to the highest levels of the government of El Salvador. Moakley Commission reports were used as trial evidence in the first-ever convictions of Salvadoran military personnel for human rights crimes.

Congress used the commission's findings to cut military aid to El Salvador, forcing the government to negotiate with the FMLN to end the war. Moakley then became a significant figure in the peace talks, most notably through a historic visit behind the lines to meet with FMLN leaders. His willingness to trust the guerrillas was a breakthrough moment on the road to peace—the FMLN finally believed that the U.S. would back an agreement—and, in January of 1992, both sides signed accords that ended the violence.

Search for Justice Continues

Congressman Joe Moakley led a congressional investigation into the matter and found that the Salvadoran military had ordered and carried out the murders. Currently, the Jesuit case is being reprosecuted in the Spanish courts by the Center for Justice and Accountability and the Spanish Association for Human Rights (APDHE).